Cost of living crisis fuels child poverty

Lily Plass

26 November 2024, 8:40 PM

Photo: Cottonbro studio

Photo: Cottonbro studio The hidden cost of childhood poverty can have long-term consequences, according to a report released by the NSW Council of Social Services (NCOSS).

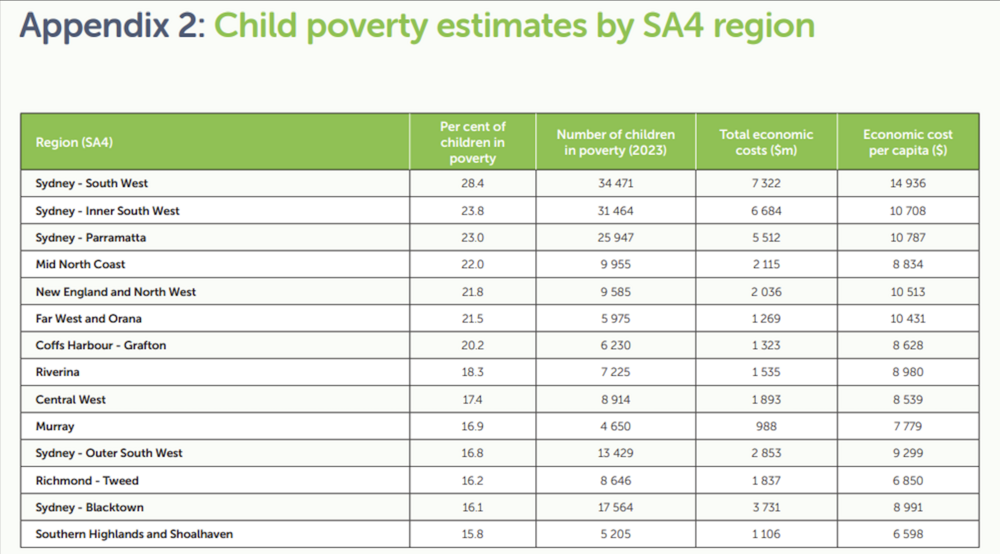

According to the report, 21.5 percent of children in Far West NSW and Orana region are in poverty, while in the Central West NSW, it is 17.4 percent of all children.

Childhood poverty can have a long-term impact on a person's trajectory impacting their physical and mental, educational outcomes, and income as an adult.

Meanwhile, the economic impact that childhood poverty has is equivalent to $1.89 billion per year in the Central West and $1.27 billion per year in the Far West.

The NCOSS captures the economic impact child poverty can have. Photo: Lasting Impact: The Economic Costs of Child Poverty in NSW (NCOSS)

"Child poverty hurts us all, it robs children of their future and steals $1.9 billion from the Central West economy every year," NCOSS CEO Cara Varian said.

Across the state that cost translates to $60 billion per year.

Ms Varian hopes the report will be a "lightning bolt" for government action.

"This report is the first in Australia that the economic costs of child poverty have been systematically quantified," Ms Varian said.

She added that after the cost of living spiked in 2023, groups of people, including those in regional and rural areas struggled to make ends meet.

"We live in one of the world's wealthiest nations - poverty is preventable and this research shows the immense economic opportunity available to the NSW government if it takes the steps necessary to avoid the long-term consequences of child poverty."

In the Western Plains area, Gilgandra and Walgett were the Local Government Areas (LGAs) with the highest rate of children in poverty, according to a report released by NCOSS and the National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling (NATSEM) at the University of Canberra in 2021.

In both areas, 21 percent of children under 14 were economically disadvantaged.

Cobar was the LGA with the lowest number of children at economic disadvantage at six percent.

Ms Varian added that poverty in remote NSW is usually experienced differently than in metropolitan areas, including limited or no regular access to services such as health, education, and transport, higher rates of isolation, and lower incomes.

"The NSW government made a great announcement this year to invest in affordable social housing and we need to see more of that."

Other solutions the NCOSS suggested included substantially increasing base rates of income support payments, guaranteeing all children access at least three days a week of quality and affordable childcare, and committing to joint decision-making to empower First Nations communities in the design and delivery of services.

"If we don't address childhood poverty, we submit intergenerational disadvantage at great cost, not only to our children but also our society and the economy," Ms Varian said.