Inequitable spending on health results in much poorer outcomes in the bush

Kristin Murdock

09 January 2024, 8:38 PM

The report has brought a call for reform.

The report has brought a call for reform.A snapshot of regional health recently undertaken by the National Rural Health Alliance (NRHA) shows rural men are 2.5 times more likely, and rural women 2.8 times more likely, to die from potentially avoidable causes than those in urban areas.

They are sobering statistics, yet the funding for rural health continues to lag behind that spent on those living in the cities.

The snapshot shows that small rural towns of less than 5000 people have access to almost 60 per cent fewer health professionals than major cities per capita, indicating continuing workforce and access challenges in rural areas. Major cities have more choice and more general practitioners and other health practitioners providing primary care compared to large regional centres, small rural towns, remote areas and very remote areas.

On releasing the report, NRHA Chief Executive Susi Tegen said it wasn't good enough.

“There is clear evidence that per-person spending on healthcare is not equitable, and that this inequity is contributing to poorer health outcomes in rural areas,” Ms Tegen said.

In 2023, the Alliance commissioned a report that found there is a $6.55 billion deficit in health funding for rural Australian communities, equating to almost $850 per person, per year.

This includes funding for public hospitals, private hospitals, Medicare, pharmaceuticals, dental care, the NDIS, aged care, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health care, primary health networks and the Royal Flying Doctor Service.

“The biggest deficits are in accessing primary health care, which then leads to higher rates of costly and potentially preventable hospitalisations and increased hospital expenditure. This is a sad reflection on the rest of Australia, when not every citizen has the same access to a basic healthcare need," Ms Tegen said.

From the NRHA report

Narromine Mayor and Chairperson of the Alliance of Western Councils (AoWC), Craig Davies, said healthcare was the number one issue for most people in the Western Plains.

"We know we can't have access to the same level of healthcare as you can get in large cities, and that new technology is incredibly expensive," Mr Davies said.

"But we should have better facilities locally and it is a constant concern for Alliance of Western Council members."

Mr Davies said the AoWC is working with Charles Sturt University in Dubbo to establish a system to attract students from western regions to study medicine and, as part of their training, to be mentored by doctors in their own towns.

"We put this proposal forward with support from all 13 councils in the Alliance," Mr Davies said.

"At the moment it hasn’t been approved, but we are focusing on health at our February meeting and hope to have several stakeholders in government and the health industry present."

Meanwhile, the health of rural Australians is impacted by disparities in rates of health and behavioural risk factors including higher rates of overweight and obesity, smoking, risky alcohol consumption, some illicit drug use and psychological distress.

Poorer diet, including inadequate fruit consumption and elevated consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks, as well as lower levels of physical activity, also contribute to the imbalance.

The NRHA report also found rural people experience higher rates of family, domestic and sexual violence. The health of rural mothers and babies, over their lifetime, is also negatively impacted by more women smoking during pregnancy, more babies being born prematurely, and lower rates of exclusive breastfeeding (except in Indigenous infants).

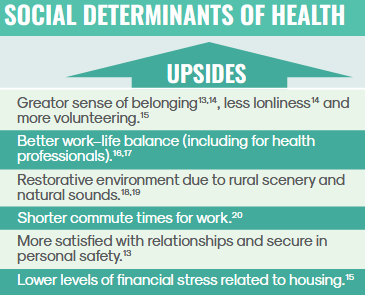

Burden of disease is also taken into account in the report. Put simply, this is a holistic measure of the impact of disease and injury in a population, taking both the effect of living with a disability and death due to disease or injury. Total burden of disease increases with remoteness, with it being 1.4 times that of major cities.

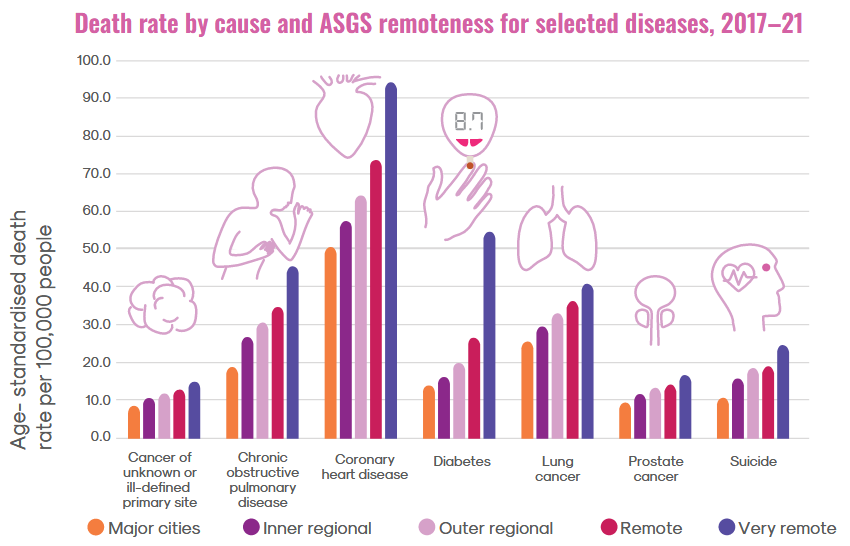

When comparing disease burden between remoteness categories by specific types of disease, there is a clear trend for disease burden increasing with remoteness for coronary heart disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lung cancer, stroke, suicide and self-inflicted injuries, and type 2 diabetes.

With such a poor report card on regional health, Ms Tegan said there is a need for change.

“The statistics show that the further you are from an urban setting, the more likely you may die of disease due to various factors, including the tyranny of distance and workforce shortages.

“Fit for purpose funding is critical to ensure that the necessary policy and infrastructure is in place.

“We look forward to a rural health system reform that reflects population health need, and place-based and led planning and service delivery, to address this discrepancy of health care access,” she said