Marking History Week 2021

Lee O'Connor

11 September 2021, 4:59 AM

It's History Week and this photo (taken by Sam Hood in 1932) is a reminder of regained freedoms.

It's History Week and this photo (taken by Sam Hood in 1932) is a reminder of regained freedoms.Amid all the fuss around the pandemic, you may have missed it, but tomorrow is the final day of History Week 2021 in NSW.

This year's theme, From the Ground Up, was suggested by the Addison Road Community Organisation and member Mina Bui Jones said, "It’s a reminder of the importance of place and Country; of the fundamental connections between specific environments and human endeavours.

"But it also suggests people’s histories, local histories, community histories — stories from the streets and from the soil that provide the material and the momentum for the making of history.”

The week kicked off on 4 September after an official online launch on Friday 3 at the Premier's History Awards, organised with the State Library of NSW.

Five authors of published historical work received $15,000 each and State Librarian John Vallance said: “It’s not often that historical writing goes beyond what we expect, and challenges us, without being relentlessly didactic, to think about our futures before we have to live in them. In their own ways, all this year’s winners do just that.”

To find out who won what go to https://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/about-library/media-centre/winners-announced-nsw-premiers-history-awards-0

Back home at ground level where our communities have been grappling with life in lockdown, along with the usual practicalities of life, it is likely that History Week was entirely unnoticed or celebrated in your town even as the pandemic forces us to think about what our futures might look like.

But the present soon becomes the past and it won't be long before historians are writing about what happened across Australia during this latest plague. Our descendants will be looking at today's media reports, medical journals and political records to piece together how we behaved this time around.

We took a little time to put our pandemic into historical perspective by consulting the oft-disputed wisdom of Wikipedia and their list of epidemics and pandemics with at least one million deaths.

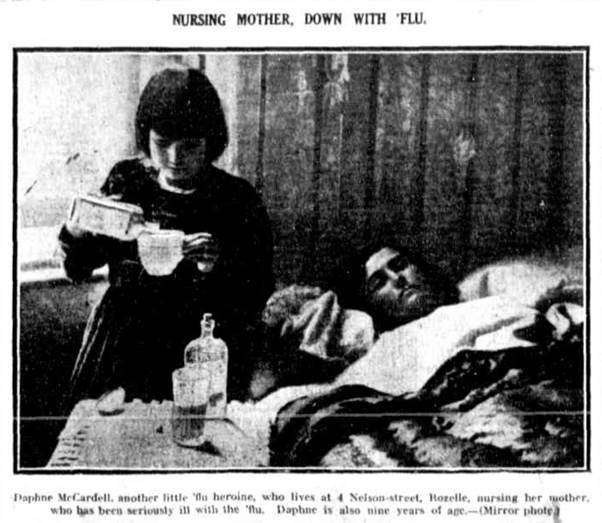

Caption: Daphne Cardell, another little 'flu heroine, who lives at 4 Nelson Street Rozelle, nursing her mother who has been seriously ill with the 'flue. Daphne is also nine years of age. - (Mirror photo)

The first recorded plague was the Antonine Plague between the years 165-180, and involved an outbreak of smallpox or measles which claimed between five and ten million lives across the Roman Empire, or at least 25% of the population.

This was followed a few hundred years later by the Plague of Justinian, a Bubonic plague which claimed up to 60% of the European population.

There were a further eight pandemics in various parts of the world, with repeat appearances of smallpox [until someone developed a vaccine], Bubonic plagues and a Mexican variety called Cocoliztli before the first truly worldwide Cholera epidemic from 1846-1860.

If Wikipedia is to be believed, there have been no less than six other pandemics since then, including a number of influenza outbreaks and the HIV/AIDS epidemic which began in 1981 and continues to wreak havoc in some parts of the world, claiming the lives of more than 36 million people up until last year, making it the fourth most deadly on record.

Ranked number one is the Black Death - the Bubonic plague which kicked somewhere between 75 and 200 million people across Europe, Asia and North Africa between 1346 and 1353.

The current COVID-19 pandemic is so far the sixth worst on record.

When it comes to history repeating, not only are we shocked and horrified at the arrival of each new wave, but we now know the methods of responding to and dealing with plagues also tend towards déjà vu.

Social isolation, overwhelmed health services, disagreements between states over border closures, tight government regulations and even mask wearing have all been seen before.

As the Royal Australian Historical Society reminds us, "A signal moment was ‘Mask Day’ – 3 February 1919."

"A swathe of proclamations around that time led to the closure not only of public, private and denominational schools, but also churches, libraries, theatres, music halls, pubs and racecourses. Such restrictions on public gatherings and business activities drastically affected communities, congregations and local economies."

Peter Curson and Kevin McCracken, from the Department of Human Geography at Macquarie University published a paper entitled, 'An Australian perspective of the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic' where they describe many of the impacts of what is known as the Spanish Flu.

'Thousands sought popular cures and medicines. Many people rebelled by circumventing the quarantine blockade at state borders or refusing to wear masks. Waterside workers refused to unload ships for fear of infection and some public workers demanded ‘epidemic pay’.'

'People shunned outsiders and interstate visitors, fearing they were a potential source of infection.

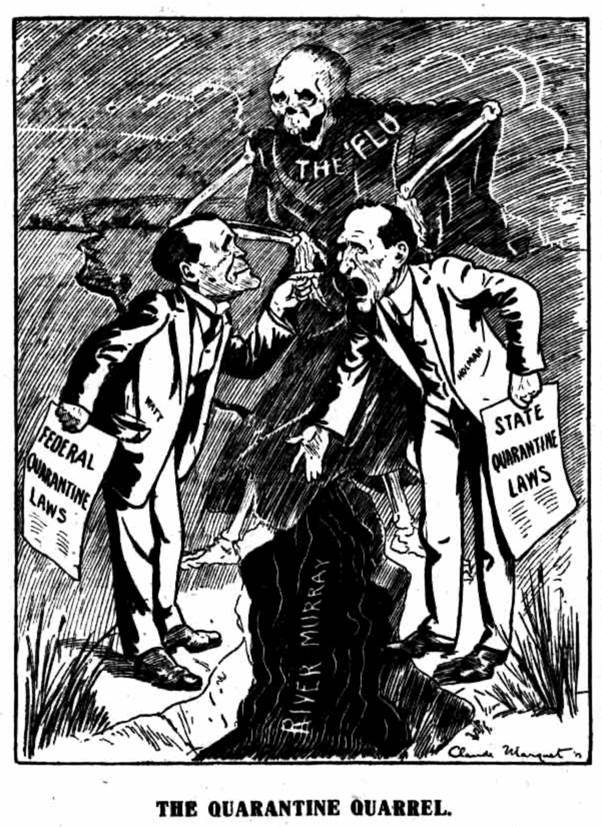

'The pandemic caused disputes between all the states and between the states and the Commonwealth over border closures, differing policies of border controls and quarantine, interstate transport links, and the quarantine of returning servicemen.

'Eventually, cooperation between the states and the Commonwealth authorities was abandoned, with each state imposing its own conditions and organising its own containment policies.'

*Image from Labour News, 12 April 1919.

The reassuring thing about historyrepeating is that it also shows how societies learn and innovate in response to every pandemic and bounce back to regain their freedom.

Perhaps you can take a moment during the final hours of History Week 2021 to record your own experiences of this plague 'From the Ground Up', and put it away for posterity.