Remembering a boy from Quambone this ANZAC Day

Liam Mulhall

24 April 2023, 9:26 PM

A young Aboriginal man from Quambone made his mark as an ANZAC

A young Aboriginal man from Quambone made his mark as an ANZACANZAC Day is a time of reflection and celebration.

Remembering those who fought in the 'Great War' and the conflicts that followed, and celebrating their stories is how we make sure they are never forgotten.

On this ANZAC Day, we reflect on the story of a young man named Dick who showed unfathomable bravery and left for war never to return home.

This is the story of Richard "Dick" Kirby, who was born on 11 November 1890 in the small western NSW town of Quambone.

The son of an indigenous woman and a British immigrant Dick's early days were spent mucking around with his two brothers Robert and George having fun in the bush and enjoying a simple life living off the land.

As he grew older he worked as a station hand, working on properties throughout the region.

Upon World War I ("the great war") breaking out in 1914, the sense of excitement and adventure to a distant land across the world proved too alluring for the small-town farm hand.

So on 23 July 1915, Dick travelled down to Dubbo to enlist in the Australian army.

Indigenous not allowed

It is estimated that around 1,000 indigenous Australians fought in World War One, however, accurate numbers are impossible to determine.

The 1903 Defence Act stated in relation to army enlistment that "Aborigines and half-castes are not to be enlisted. This restriction is to be interpreted as applying to all coloured men."

In the early years of the war, this was enforced quite heavily and in the Gallipoli campaign, just seventy Indigenous soldiers took part in the battle for the Dardanelles - with Dick amongst them.

Mark Daniels is Dick's great nephew, and he believes his features and builds helped him slip through the cracks.

"He had Indigenous features, you look at photos of him and that’s quite obvious," said Mark. "But I think because he was a 'half-caste' and had a certain build the officers let him join."

In the weeks that followed Private Kirby packed up and left Quambone for Sydney Harbour where he would set sail for the Gallipoli peninsula on the HMAS Argyllshire on 30 September 1915.

Gallipoli and the Somme

There could be no preparation for the horrors that awaited Dick and the 20th battalion on the Turkish beaches, or any of the ANZACS for that matter.

And despite the Gallipoli campaign ultimately resulting in an allied defeat Dick was one of the lucky ones to escape the conflict alive.

It is estimated that 8,141 ANZAC troops died at Gallipoli.

He then travelled to France where he spent a short time in an allied hospital to be treated for an illness he sustained in Turkey.

Following his recovery he re-joined the 20th Battalion on the Western Front along the river Somme for the battle of Pozieres.

The small village in the north of France acted as a key strategical position during the war due to its position atop a ridge and prior to 23 July 1916 the Germans held it.

There were less than seven weeks of fighting at Pozieres and the Australian troops took the village, however, it was disastrous.

There were 23,000 Australian casualties as a result of the battle, prompting Australian historian Charles Bean to write that Pozieres "is more densely sown with Australian sacrifice than any other place on earth."

Lance Corporal Kirby

It is told that Dick Kirby was "one of the best"

"From all accounts, he was a really good soldier," said Mark Daniels. "And I know it's not a job, but in that sense, he was very good at his job."

Following his service in Gallipoli and at the Somme Private Kirby was promoted to Lance Corporal on 22 May 1917.

As a Lance Corporal, Dick survived the Battle of Menin Road and the Battle of Poelcappelle - key conflicts in the Battle of Passchendaele in Belgium.

And as the war wore on Dick was eventually wounded during the Spring Offensive of 1918, sustaining a gunshot wound to the neck after performing a trench raid.

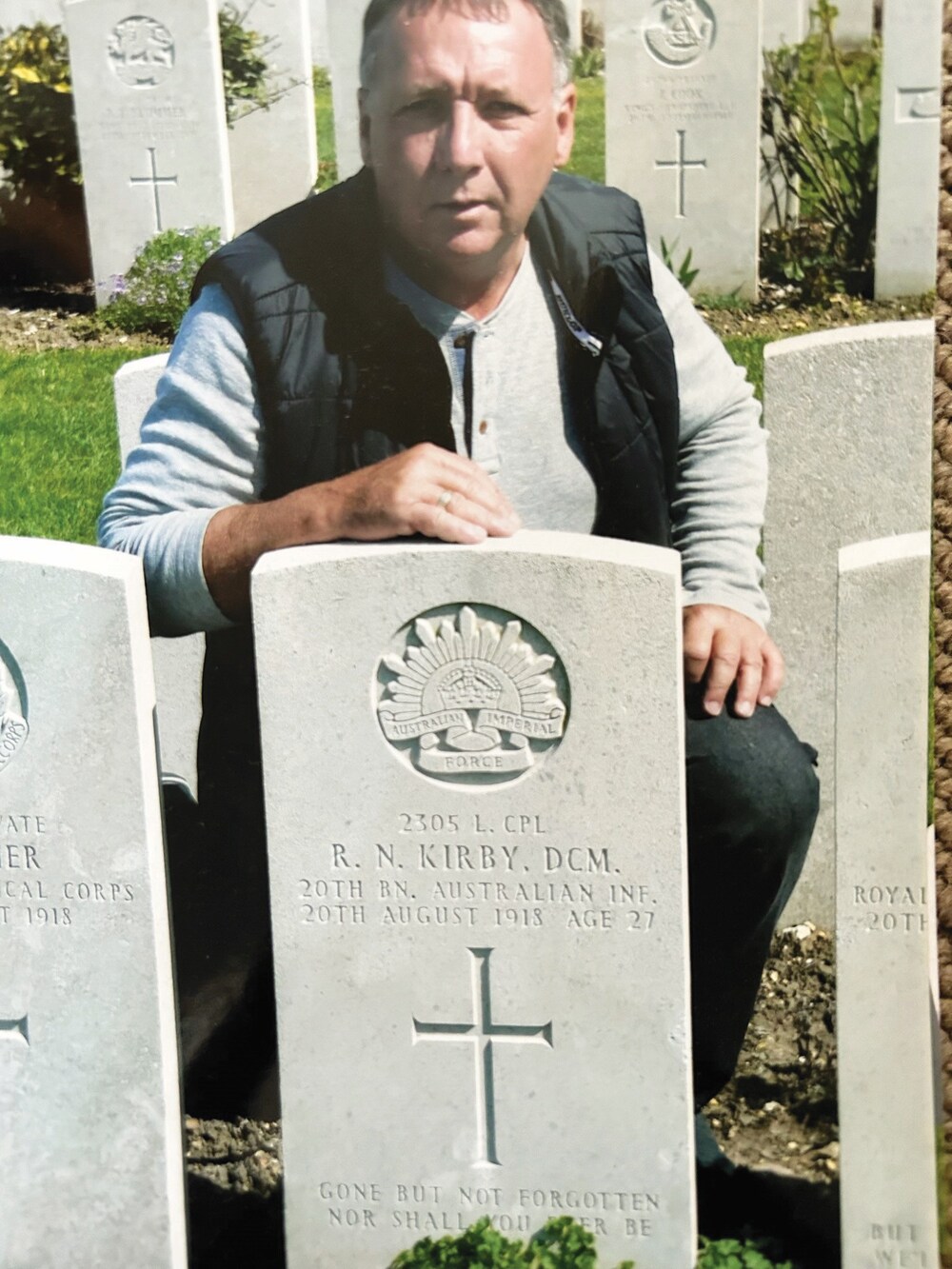

Mark Daniels with his ancestor's war grave. IMAGE SUPPLIED.

"He bounced back from the injury quite well though and it didn’t take long before he was back on the front," said Mark Daniels.

"He was the person that would go out into no-man's-land to try and gain a point, then the rest of his team would follow."

Dick would return to the Western Front in time for the Battle of Amiens on 8 August 1918, as a part of what is now called "The Last Hundred Days."

The 20th Battalion was stationed in Rainecourt, East of Amiens, and on 11 August 1918, they were held up by heavy machine gun fire from the German forces on their left flank.

Several casualties ensued, however, it was a Lance Corporal from Quambone who would make the decisive move to turn the tide.

Dick rushed the German machine gun station single-handed, and despite sustaining a bullet wound to the head he captured the station and held fourteen of the enemy to a ceasefire until allied support could arrive and consolidate the capture.

Dick was quickly sent away to the US Army General Hospital in France to be tended to, however, the injuries proved too costly, and nine days later on 20 August 1918, Dick Kirby was pronounced deceased at age 27.

Robert Kirby is remembered in Quambone where he is listed with other fallen soldiers in the Quambone Hall.

Legacy

For his efforts in Rainecourt, Dick was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM), regarded as second only to the Victoria Cross, in the highest awards for gallantry.

He was awarded it for "conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty."

To this day he is just one of three indigenous soldiers to be awarded a DCM during World War One.

Dick Kirby fought for a king and country that never fought for him.

As an Indigenous man, he was never once counted in the census and even if he had returned home he would not have been granted the life that many soldiers got post-war.

When they returned home they weren't allowed to have a drink with their brothers at the local or apply for land under the soldier's scheme.

Quite simply, Indigenous soldiers were treated equally on the battlefield and discriminated against away from it.

Lest we forget.