There's Something in the Water, We Just Can't Find it Yet

Laura Williams

03 September 2021, 5:00 AM

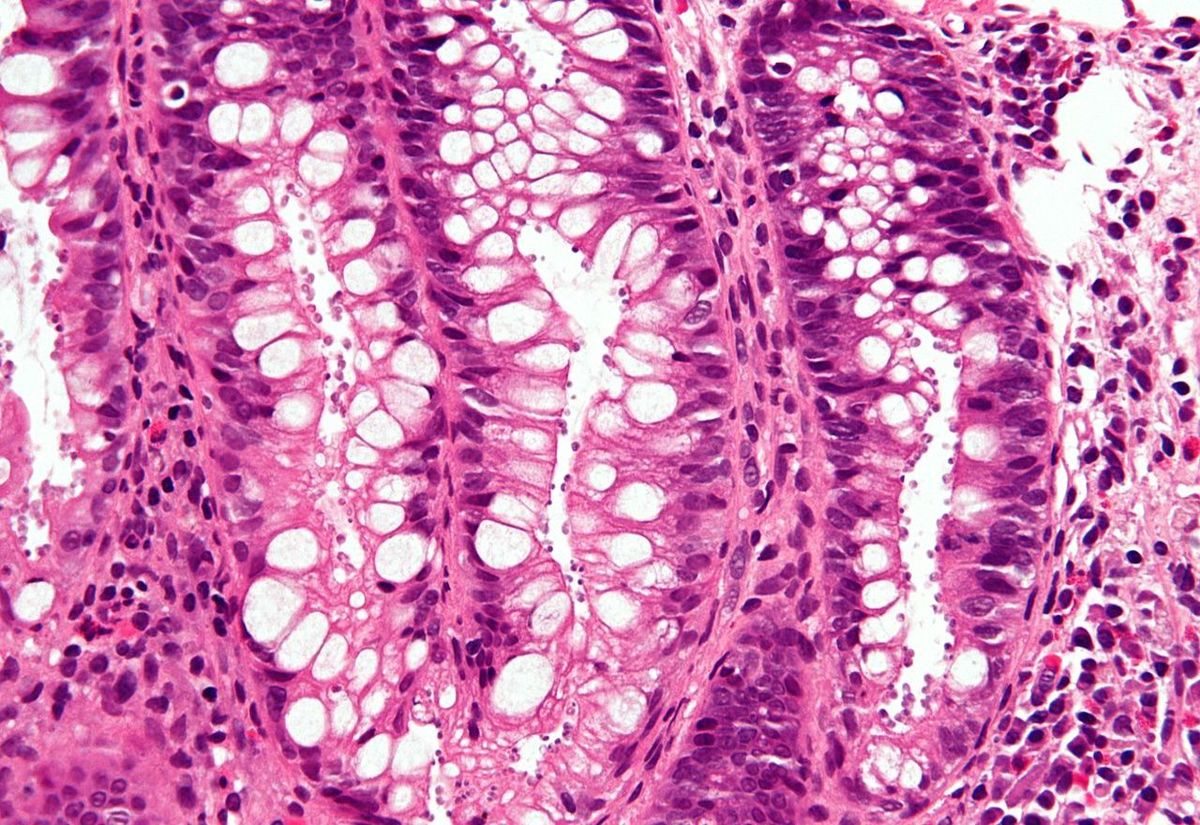

Cryptosporidium is incredibly tedious to identify in water samples, yet consuming just one microbe is enough to make you ill.

Cryptosporidium is incredibly tedious to identify in water samples, yet consuming just one microbe is enough to make you ill.The benefits of current research into the detection of parasites in water is two-fold: maintaining the safety of local water supplies while providing more efficient detection of COVID-19 in wastewater samples.

While cryptosporidium might be difficult to pronounce, according to NSW Health the disease is simple to contract, as simple as drinking a glass of water with as little as two microbes of the parasite.

Though it might seem low on the priority list in a time where COVID-19 has stolen the show, rural communities are particularly vulnerable to the disease, where water supplies affected by animal contamination or heavy rain after drought are highly susceptible.

Leading the study into more efficient methods of testing is Professor Ewa Goldys, who says that the current testing method is as rigorous as detailed as putting a microscope to fragments of water and searching for the harmful microbes.

“This new method lowers the cost of water testing and makes it more broadly available,” Professor Goldys said.

The proposed new method of testing involves adding a fluorescent agent to the water samples, which, when combined, shows clear indication of detection. Rather than analysing single samples, it will allow the process to be streamlined, testing across 400 samples at a time.

“In addition, we believe this technology could be applied to the detection of Covid-19, which currently takes up to 11 hours to get results from wastewater samples – much of which is often time spent transporting the sample to the lab where all the specialised equipment is located,” she said.

For rural communities especially, the time spent of samples in transit to be tested at larger city centres poses risk to vulnerable communities. If a regional or remote community detects cases of COVID-19 in sewerage samples, it is likely that those cases have been transmitted in the community for much longer than that of the city, due to those travel times.

Until the funding is granted to approve further research to adapt the method to focus on COVID-19 testing, Professor Goldys has her eyes set on creating more effective ways of purifying water.

“Purification sounds easier than it is as many of the pathogens are not easily removable, especially cryptosporidium. There’s so much water to test as well, it really is a needle in a haystack problem,” she said.

While at the best of times, ingestion of the microbes are enough to cause gastrointestinal disorders, for the immunocompromised failure to detect its presence in the water could cost a life.

“Australia is vulnerable to this disease especially because of its kangaroo population, but it is also prevalent everywhere in the world, and the lose const technologies could benefit us, benefit developing countries and benefit rurally communities who could test locally,” Professor Goldys said.

While research continues into the study, the horizon is looking more promising at closing the health gap between rural and city communities.