Tipperary Flying Mile; a record-breaking ride

Liz Cutts

15 October 2022, 11:01 PM

Official timekeepers, police and mechanic ready to record speeds during the Tipperary Flying Mile. (image; V. Mills)

Official timekeepers, police and mechanic ready to record speeds during the Tipperary Flying Mile. (image; V. Mills)Sixty-five years ago, in the endless quest for speed, a world record was chased, won and briefly held in Baradine.

The dates of 28 and 29 September, 2022 marked the unheralded anniversary of this unique and incredible event.

Since the motor engine was invented there has been a worldwide passion to break speed records and for a short period in its history Baradine was at the centre of an attempt at the World Land Speed record.

Prior to 1955, oil companies did not involve themselves in motor sport. However, Commonwealth Oil Refineries (COR) was at that time owned by British Petroleum (BP) who believed it would be good for marketing to sponsor motor racing. They thought that winning a few speed records with cars using their products would be good advertising and so the idea of the 1957 speed trials was born.

In early 1956, Graham Hoinville, on behalf of BP, began scouring the country for a satisfactory location to hold Australian Land Speed Record attempts. BP was willing to underwrite the exercise, however organising the venture was quite another problem. It took Hoinville over a year to eliminate all but one site; a dead-straight four-mile stretch of road beside the Coonabarabran to Baradine railway line.

The road, which ran past the gates to the property of Tipperary, came to be known as the Tipperary Flying Mile.

Drivers were invited to compete in what was to become the 1957 BP-COR Speed Trial. Well-known racing drivers of the day were contracted for the event including Lex Davidson (Ferrari), Ted Gray (Lou Abrahams Tornado), Len Lukey (Cooper-Bristol and Customline), Derek Jolly (Decca Special), Jim Madsen (Cooper-BMW), John McMillan (Ferrari), Jimmy Johnson (MGA) and Roy Blake (Cooper-JAP).

The date was set for Saturday, 28 and Sunday 29 September, 1957. The then Coonabarabran Shire Council and NSW Police agreed to the proposal and arrangements were made to close the road for two days. The road was newly sealed and had no white line and, as this was considered essential, painters were employed to paint a line three miles long by hand!

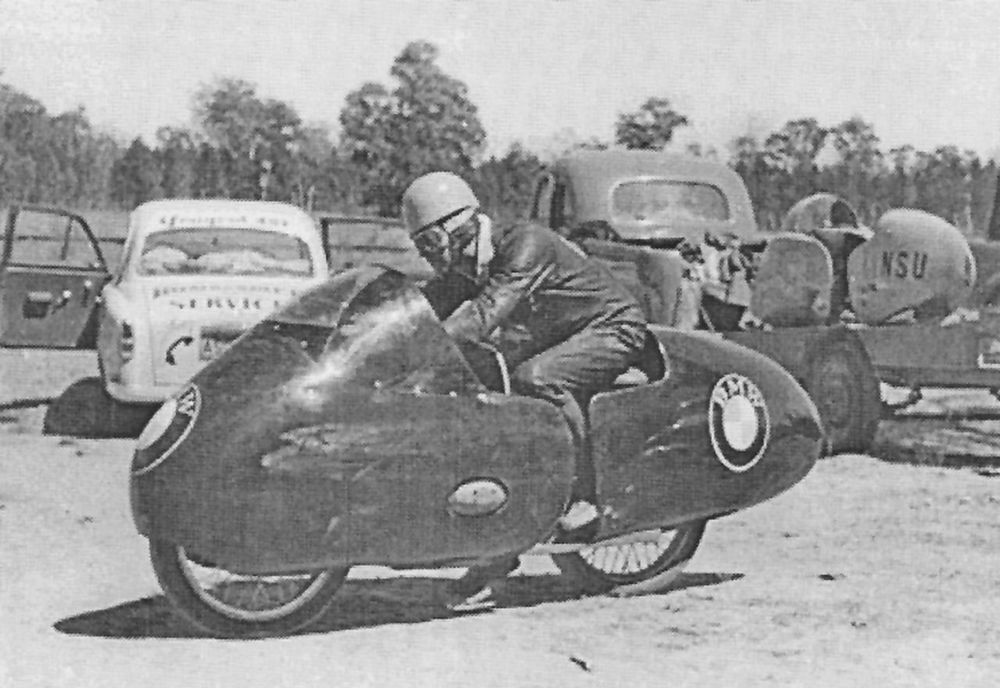

At the last minute it was decided to invite motorcyclists. Jack Forrest (BMW), Trevor Pound (Eric Walsh 125cc BSA Bantam), Jimmy Guilfoyle (BSA) and Jack Ahearn, with his 350 Manx Norton and a 250cc NSU Sportmax, rolled up to compete. Sidecars were represented by Frank Sinclair’s 1080cc Vincent and Bernie Mack’s 500 Norton.

Three thousand spectators lined the road to watch Australia’s top ten racing cars attempt to break existing national records over a flying kilometre along with motorcyclists setting new records for a flying half mile.

Strong winds and bushfires swept through the district threatening event postponement, with the added hazard of loose gravel being blown onto the sealed road from dirt tracks leading to properties. The bushfires continued to blaze but the wind had dropped by the time drivers lined up for their shot at glory.

ABOVE: Record breaker, Ted Gray lines up at the start of the 1957 Tipperary Flying Mile time trials in his Tornado Special. (image; V. Mills).

Records toppled

Amazingly, almost every national speed record for cars and motorbikes fell over the memorable weekend in September in the first mass attack ever organised in Australia.

The hand-picked team of drivers and riders set new marks and records toppled as attacks were made on the flying kilometre.

In accordance with Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA) regulations two consecutive runs in opposite directions had to be made within an hour and timed to within 1/100th of a second. John Crouch and George Hutchings were the Confederation of Australian Motor Sport (CAMS) observers.

The newly sealed surface was in top condition and allowed high road speeds, but it was only 18 feet wide and had a pronounced crown.

The usual practice is to hold speed attempts at dawn, when the weather is calmest but on this occasion the runs were made in the middle of the day. As the winds were so blustery on the first day, motorcycle attempts were postponed until the Sunday.

In Class C, for cars with 3001-500 cc engines, Victorian Ted Gray recorded the fastest time in the Lou Abrahams Tornado with a fuel injected Chev 4.3 litre engine that reached 157.53mph (252.05 kph). The other Class C car, a 3.51 Maserati driven by John McMillan, finished with a mean speed of 152 mph (244.62 kph).

Lex Davidson had Class D (2001-3000cc) all to himself. He was using half-worn tyres following the practice adopted by Dunlop of using very little depth of rubber on high-speed tyres. He finished with an average of 155.99mph (249.58kph) breaking the Class D record of 143mph comfortably.

The Class E (1502-2000cc) record of 113 mph was Len Lukey’s target in his immaculate Cooper-Bristol. Len and his team fitted an anteater-like snout to the green car improving both appearance and speed and also enclosed the sides of the cockpit. Although plagued by overheating, Lukey averaged 147.46mph (235.94 kph). This was voted the best run of the meet.

ABOVE: Drivers line up for the 1957 Tipperary Flying Mile time trials. (image; V. Mills)

Limelight

Lukey again stole the limelight when his incredible Customline notched an opening run of 130mp (209 kph) aided by a tail wind. Observers believe that if the antiquated timing equipment used by BP hadn’t become temperamental, Len might have got an even higher result.

The existing Class F record of 103.5mph (165 kph) would most likely have been broken by Jim Johnson in his MG special. His tragic death in an accident on the Saturday was a blow to motor racing.

Derek Jolly came from South Australia with his Climax engine Decca Special to take the Cass G (751-1100cc) at 116.75mph (186.6kph). His little Decca was the only sports car taking part.

Class H (501-750cc) went to Jim Madsen’s Cooper-BMW at 109.97mph (175kph) and Class I (351-500cc) to the Roy Blake/Steve deBord Cooper 500m, which screamed through the traps at 102.47mps (164kph).

Motor cyclists Jack Forrest, Jack Ahearn, Frank Sinclair and Bernie Mack split up the bike records between them. Ahearn took the 251-350cc class with his Norton at 125.68 mph (202kph) and the 175-250cc class with his NSU at 121.25mph (195kph).

ABOVE: Racing driver and garage proprietor from Leichhardt, 29-year-old Jim Johnson was killed instantly when his MG Special crashed into a truck during an early morning trial speed run before the official start of the Tipperary Flying Mile.

Frank Sinclair took the big sidecar class with his HRD at 124.25mph (199kph) with Bernie Mack’s making easy work of the 351-500 sidecar class with 122.22mph (196kph).

Flashy cars, glamorous women and a collection of racing motorcycles, Jack Forrest was the embodiment of a dedicated, risk-taking racer. Born in Wellington NSW in 1920 he has been described as your typical ‘Aussie larrikin’ and for just a few hours he held the title as the fastest man in Australia.

In an effort to raise the gearing of his BMW Rennsport, Jack and his mechanic Don Bain fitted a larger-section rear tyre.

On the first Tipperary Flying Mile practice run, the tyre grew so much due to the centrifugal force that it jammed against the swinging arm, melting the rubber, locking the rear wheel and depositing a skid mark on the road that was still visible more than twelve months later!

With no other rear tyre available, Baradine garage owner, Vane Mills vulcanised a patch on the area which had worn through to the canvas. With his patched-up rear tyre, Forrest blasted through the speed traps at 152mph (244kmh), but the BMW was wobbling almost uncontrollably.

ABOVE: Jack Forrest held the land speed record riding his BMW for a brief time.

But the next day, Sunday, 29 September Ted Gray pushed his 283 cubic-inch V8 Corvette-powered ‘Tornado’ to an Australian Land Speed record of 157.7mph (253.7kmh).

Never again would motorcycles be able to match the speed of racing cars in Australia.

There is no doubt that the 1957 BP-COR Tipperary Flying Mile speed trial was a significant chapter in Australian motor history. It was an event that achieved seven Australian land speed records for racing and touring cars and five records for motorbikes. Nationally, this feat has never been equalled and is a worthy claim to fame for Baradine and the Warrumbungle region.

SHOP WEST