Youth crime prediction tools fall short for Aboriginal children

Kristin Murdock

22 December 2025, 8:40 PM

New analysis reveals that predictive risk models used to identify young people at risk of early contact with the justice system perform significantly worse for Aboriginal children, raising alarm about potential bias and unintended consequences for First Nations youth.

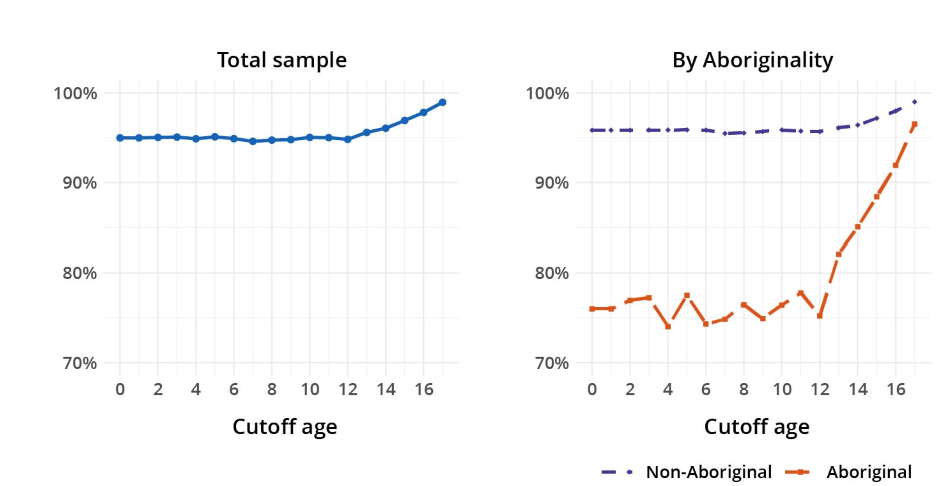

The NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (BOCSAR) study by Min-Taec Kim and Fan Cheng found that model accuracy dropped as much as 22 per cent for Aboriginal young people compared with non-Aboriginal cohorts - a shortcoming researchers described as “model bias” with serious ethical risks.

“Any practical use of these models must consider ethical risks such as misclassification, stigma and unintended consequences,” the report authors said.

Aboriginal children are already over-represented in the youth justice system, and the latest findings underscore concerns that data-driven tools could entrench disadvantage rather than help prevent justice contact.

While there has been no formal government response to the BOCSAR bulletin itself, regional leaders have continued to weigh in on youth crime policy more broadly, particularly in rural and regional NSW.

Jamie Chaffey, Member for Parkes, has previously said regional communities cannot afford delays in youth crime responses, arguing that meaningful solutions must be evidence-based and supported by services on the ground.

Barwon MP Roy Butler has also stressed that youth crime is complex and well-understood, repeatedly pointing to the need for early intervention, community safety measures and support services rather than simplistic punitive approaches.

Accuracy of prediction models for first criminal justice contact before age 18 by age cutoff, showing the proportion of correct predictions for the total sample, Aboriginal children, and non-Aboriginal children

Parliamentary concern over punitive approaches

Concerns about the impact of youth justice responses on Aboriginal children were formally raised in the NSW Parliament as recent as late November.

In the Legislative Council, Greens MLC Sue Higginson moved a motion criticising the practice of locking children behind bars, arguing it does nothing to address youth crime, increases the likelihood of reoffending, disproportionately impacts First Nations children, and is not consistent with international law.

Her motion also criticised the Minns Labor Government for adopting what she described as a “tough on children and crime” framework without clear supporting evidence, and for failing to adequately listen to First Nations people, legal experts, the United Nations and justice specialists.

Ms Higginson called on the government to change its approach by consulting directly with First Nations communities and peak bodies, responding comprehensively to the findings of an independent review, and raising the age of criminal responsibility to at least 14 without exception.

Researchers and advocacy groups have long warned that punitive youth justice responses risk worsening long-term outcomes for children, particularly Aboriginal children, without addressing the underlying causes of offending.

The BOCSAR bulletin reinforces those concerns, noting that predictive tools may appear accurate while masking significant bias against specific groups.

The findings come at a time when governments are increasingly looking to data-driven tools to guide early intervention and youth justice policy.

Researchers caution that without careful oversight, cultural understanding and ethical safeguards, predictive models risk reinforcing the very inequalities they are intended to reduce.

While the BOCSAR bulletin does not indicate the models are currently being used operationally, the findings raise questions about how predictive tools might be applied in future policy and early-intervention settings.

The entire report can be read here.