Smart farming starting to pay off for western plains croppers

Ainsley Woods

13 August 2025, 2:40 AM

Weeds remain one of the biggest threats to cropping in the Western Plains, with local growers battling species that are becoming tougher and harder to kill.

However, new research shows there is good news, with smarter control methods starting to turn the tide.

Sow thistle has emerged as the most problematic weed across the region, followed closely by other hard-to-kill species such as windmill grass, fleabane and ryegrass, the four most persistent threats for local farms.

Across the region, farmers say the fight is far from over, with new species emerging and old foes becoming more aggressive as they adapt to control measures.

In many cases, weeds that were once seasonal are now persisting year-round, putting extra pressure on time, resources and moisture, a precious commodity in local farming.

Trangie grain grower and cotton farmer, Richard Quigley, says this shift comes down to natural selection.

“Most of those are summer dominant weeds, but we’re finding they’re evolving and no longer confined to a season.

"They’re starting to grow all year round, particularly Sow thistle and ryegrass.

“Weeds are adapting because, at the end of the day, we’re providing the same or similar treatments year round. It’s natural selection, populations are starting to adapt to what we’re using.”

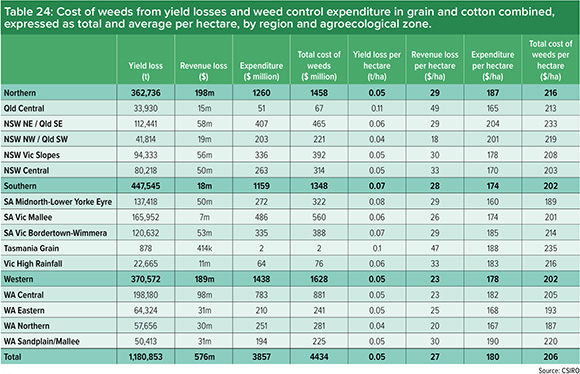

Cost of weeds from yield losses and weed control expenditure in grain and cotton combined, expressed as a total and average per hectare, by region and agroecological zone. Source: CSIRO

A new CSIRO report, backed by the Grains Research and Development Corporation (GRDC) and Cotton Research and Development Corporation (CRDC), shows weeds still cost Australian grain and cotton industries a staggering $4.43 billion a year.

But the research also highlights progress. Yield losses from weeds have dropped from 2.8 million tonnes in 2016 to 1.2 million tonnes this year, proof that integrated weed management is working.

For Quigley, weed control isn’t optional.

“It’s absolutely an investment because at the end of the day, we need to protect whatever moisture we have, it’s typically our most limiting factor.

"Weed control is a non-negotiable. Without it, we can’t grow crops sustainably, it’s that simple.”

That investment comes in many forms.

On his farm, Quigley uses “all the tools in the toolbox” – optical spot sprayers that dose only the weeds, strategic tillage, drones to map out paddocks and residual herbicides to kill weeds as seeds before they grow.

“If we can treat these weeds as seeds before they actually get going, we’ve got a lot more chance of being able to control them cost-effectively and easily,” he said.

Summer fallow weed control, a technique that conserves soil moisture between crops, has become a game changer in the Western Plains’ hot, dry climate, helping farmers plant on time and get crops established in challenging seasons.

Report Co-author, CSIRO Research Scientist Rick Llewellyn. Photo: GRDC

Quigley says the proof is in the paddock.

“We’ve been able to maintain or increase yields, which is the end goal. Where we don’t control our weeds, we see a decline in yields and profitability, that’s absolutely true.

"It’s important not to rely on one strategy, whether that be a chemical or mechanical strategy. It’s about mixing and rotating herbicides and strategies to maximise our control.”

CSIRO Research Scientist Rick Llewellyn says the results are a quiet success story.

“The only reason we’re not seeing widespread yield losses from weeds today is because of years of sustained research and grower innovation,” he said.

Farmers know the battle is ongoing. With innovation, persistence, and a willingness to adapt, the weeds might still be evolving, but so are they.